April 29, 2021

Early architectural decisions and their consequences

Plio was designed to be used by multiple organizations concurrently, each running its own programs, users, and content, while relying on shared infrastructure.

This was not a scaling concern discovered later. It was intrinsic to how Plio was expected to be adopted: different organizations operating independently, often in parallel, with no tolerance for ambiguity around data ownership or access.

From the outset, the system had to answer a hard question:

How do you allow multiple organizations to share infrastructure without sharing risk?

Multi-tenancy was the architectural mechanism through which that question had to be resolved.

Why multi-tenancy mattered early

Multi-tenancy is often treated as something that can be “added later.” In practice, this only works if early decisions do not encode single-tenant assumptions.

In Plio’s case, deferring multi-tenancy would have meant:

- Coupling users, content, and analytics to a single organizational context

- Embedding ownership assumptions directly into data relationships

- Allowing authorization boundaries to remain informal rather than enforced

- Increasing the blast radius of future schema and access-control changes

Once real programs depend on a system, these assumptions harden quickly. Retrofitting isolation later typically requires large-scale data migrations, reworking authorization semantics, and rebuilding analytics pipelines that were never designed with tenant boundaries in mind.

Designing Plio as a multi-tenant system early meant accepting architectural complexity upfront in exchange for long-term safety and clarity. This was a trade-off, not an optimization.

The constraints that shaped the design

The multi-tenant architecture needed to satisfy several constraints simultaneously:

Strong isolation guarantees

Data belonging to one organization — including users, content, engagement events, and analytics — could not leak into another, even in the presence of application-level errors.

Shared operational surface

Fully isolated deployments per organization would have multiplied operational overhead and slowed iteration. The system needed to run as a shared service.

Developer and operational clarity

The architecture had to remain understandable to a small team over time. Designs that relied on pervasive conditional logic or implicit context were likely to degrade.

Analytics and reporting correctness

Future reporting workflows would depend on tenant boundaries being explicit and reliable. Any ambiguity at the data layer would propagate into analytics and operational reporting.

These constraints ruled out both extremes: a single shared schema with soft separation, and fully isolated deployments with duplicated infrastructure.

Isolation models considered (and why they were rejected)

At this point, the design space narrowed to a critical choice:

Where should tenant isolation be enforced so that mistakes fail loudly rather than silently?

Shared schema with tenant identifiers

This model relies on a tenant_id column across shared tables.

While simple initially, it carries known risks:

- Every query must be tenant-aware

- A single missing filter can expose cross-tenant data

- Authorization bugs surface as data leaks, not errors

- Analytics queries become harder to validate

Given Plio’s use in real education programs, this level of risk was unacceptable.

Fully isolated databases per tenant

This provides strong isolation but introduces operational costs:

- Provisioning and migrating databases per organization

- Coordinating schema changes across tenants

- Complicating analytics and operational tooling

For a small team operating a shared platform, this traded one class of risk for another.

It’s worth asking the counterfactual:

What would have broken — or become dangerously ambiguous — if tenant isolation had been deferred or enforced only at the application layer?

The chosen model: schema-level isolation

Plio adopted a schema-per-organization model within a shared database instance.

Each organization operates within its own schema, while sharing:

- Application code

- Deployment infrastructure

- Operational tooling

This establishes important invariants:

- Tenant boundaries are enforced at the database level

- Cross-tenant queries are structurally difficult, not merely discouraged

- Migrations and schema changes can be reasoned about explicitly

- Analytics pipelines can rely on isolation without defensive filtering everywhere

The complexity is confined to controlled boundaries, rather than being spread across the codebase.

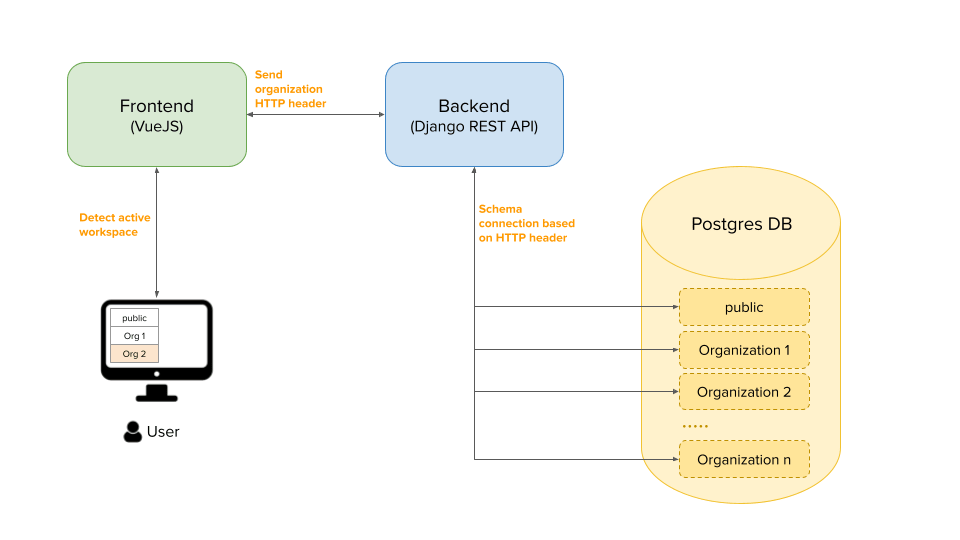

How tenant context flows through the system

Multi-tenancy only works if the tenant context is explicit and consistently propagated.

In Plio:

- The frontend operates within an organization-scoped workspace

- Requests carry explicit tenant context

- Backend middleware resolves the tenant context before any data access

- Database connections are scoped to the appropriate schema

Tenant context is resolved once, early, and treated as an invariant. Mistakes surface as errors, not silent data leakage.

Operational consequences of this design

Architectural choices only matter if they hold up under change.

What does this isolation model make easier — and what does it make harder — once the system is live?

In practice, this design led to:

- Safer evolution — new features without re-auditing every data path

- Clearer analytics contracts — reporting pipelines could rely on schema boundaries

- Reduced blast radius — failures scoped naturally to a single organization

- Easier reasoning — data ownership understood structurally, not by convention

These benefits compound as systems grow in scope and responsibility.

What this enabled — and what it deliberately did not

This design enabled Plio to:

- onboard multiple organizations safely

- support program-level reporting and analytics

- evolve toward platform responsibilities without re-architecture

It deliberately did not optimize for:

- arbitrary cross-tenant queries

- per-tenant database customization

- premature scaling complexity

Those trade-offs were intentional.

Where this fits in Plio’s broader architecture

This multi-tenant foundation underpins:

- Plio’s analytics and reporting workflows

- program-level operational reporting

- future integrations that depend on tenant isolation

For a deeper technical context, see:

- Plio — Database & Multi-Tenant Architecture Snapshot

- Plio — Program Reporting & WhatsApp Delivery Snapshot

Related reading

This page focuses on multi-tenant system design and isolation mechanics.

For additional context on how these architectural choices supported real program operations and reporting workflows, see: